The Proposed

Madison Square North/Tin Pan Alley

Historic District Extension:

Update:

A new proposal for a NoMad preservation district extension was submitted to LPC at the end of July.

NoMad. To know it is to love it.

NoMad, an area that until “yesterday” was primarily a commercial neighborhood has been changing at a breathtaking pace. Today it is a very sought after residential area thanks to its charming architecture, parks, amenities and transportation hubs.

As more and more people are seeking space to call home, developers are moving in with projects that are not always respecting the history and charm of the neighborhood.

This is one of the reasons why we need to expand the NoMad historical district now.

THE ADVANTAGES

Development is inevitable—we can’t stop it.

But under expansion of the Historic District, we can guide it for maximum benefit.

Restrictive local zoning laws are a problem for everyone, including building owners.

But being part of a Historic District will help diversify building use through a law that makes changing building use in a Historic District more flexible, thus enabling residential or mixed-use conversions.

Currently, buildings are held to current zoning restrictions, effectively delegating most building to manufacturing or warehouse space. Under existing zoning, the only way a building owner can make a profit is to demolish his building and develop the site for one of the few profitable uses permitted: High-rise hotels. Hence, NoMad is becoming HoMad.Property values increase in a Historic District and historically have much less fluctuation in a market downturn. This benefits both residents and commercial owners.

Stability is possible in a Historic District. Anxiety is rampant now—what will happen? How will the neighborhood change? How are these new high-rise hotels and rooftop bars going to affect my quality of life? With a Historic District, these wild and rapid “unknowns” will slow down.

Historic Districts help protect against unforeseen consequences.How about traffic? Congestion in our neighborhood is already a problem. We are the main area for crosstown traffic coming and going from the Lincoln tunnel. Our crosstown one-lane streets are already jammed. Now add the two block-through high-rises, and 4 hotels all being developed here, and you have gridlock all the time.

As you can see, we have everything to gain by doing this:

Quality of life

Diversity of building use

Passable streets

All the things that good city planning should ensure but doesn’t in non-Historic Districts.

Our future is up to us, and we must act quickly.

HISTORIC NOTES

The Proposed Madison Square North Historic District Extension, comprising 286 buildings from the 1840’s through the late 1930’s, clearly articulates an historical and architectural narrative indistinguishable from that set forward by the original Madison Square North Historic District Designation Report. Early 20th-century office and commercial structures, turn-of-the-century hotels and original mid-19th-century row houses, both intact or with significant historic alterations, fill the area including many noteworthy examples of a particular building type that is fundamental to Midtown Manhattan’s architectural composition but as of yet is little noted: the repurposed row house, a common building practice of the first quarter of the 20th century in which row houses were fully altered for commercial purposes and given entirely new facades.

Details:

Often in the Arts & Crafts style or a modified Art Deco and occasionally in Neoclassical variations or something more akin to the Chicago School of Design because of their austerity, these structures are a key component of this neighborhood. While they evoke their 19th-century domestic origins through scale, they were given new facades often by established and noted architects of the period including Emory Roth, William Hohauser, Henry Oser, Sommerfeld & Steckler, Charles Birge, Gronenberg & Leuchtag and George Pelham. Each of these architects is well represented in the initial district designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The Area:

Geographically, the area is clearly defined and traversed by three world-renowned arteries: Broadway, Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue. In fact, Madison Avenue’s first eight blocks are contained within this proposed the logical termination of the northern corners of the extension while the Ladies Mile Historic District defines the southern edge along West 24th Street.

Madison Square Park:

While not part of our map, the Commission could choose to either include Madison Square Park (circa 1840’s)located at the southern edge of the district, either within the proposed extension or designate it as a scenic landmark. The park was critical in the development of the area during the 19th and early 20th century and retains its mid-19th century form along with numerous significant public sculptures such as the outstanding Farragut Monument, created in 1880-81 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Sanford White.

The Buildings:

These buildings, when taken together, have an instantly recognizable physical presence, and create a sense of place quite distinct from other parts of Midtown Manhattan. Our hope is that the Landmarks Preservation Commission will move expeditiously to calendar all 286 structures and protect the full historic and architectural breadth of the Madison Square North neighborhood.

The survey review of the area surrounding the existing Madison Square North Historic District was undertaken at the request of the Society for the Architecture of the City and the Historic Districts Council, with support from the Trust for Architectural Easements. It was prompted by concerns that new development pressures are leading to the loss of important historic resources in the area.

The Survey Boundaries:

The study area is bounded by Sixth Avenue on the west, Park Avenue South on the east (excluding the buildings fronting on the avenue), West 24th and East 26th streets on the south, and East and West 34th streets on the north. The southern boundary reflects the border of the existing historic district, south of which lie Madison Square Park, and the northern border of the Ladies’ Mile historic district. North of 34th Street lies the distinct area of the garment center. Park Avenue South separates the area from the Kips Bay and Murray Hill neighborhoods, and also forms its own cohesive area – which is why the buildings that line the west side of Park Avenue South are not included in the study area. West of Sixth Avenue is a southern extension of the garment center.

THE EXISTING DISTRICT

The district represents the period of New York City's residential and commercial history from 1849 to 1930. During that time, Madison Square North evolved from a fashionable residential neighborhood into a major entertainment district of hotels, clubs, stores and apartment buildings, and then into a mercantile district of high-rise office and loft buildings. Architects whose work is represented in the district range from anonymous builders of small row houses to major firms responsible for high-rise buildings on Broadway and Fifth Avenue.

HISTORICAL FACTS

Madison Square Park opened in 1847, leading to the development of the surrounding area. From 1849 to 1865, the historic district evolved as a fashionable residential district, following the 19th-century pattern of such districts gradually moving northward along Broadway. Other houses were erected on the side streets. Construction of the luxurious Fifth Avenue Hotel on Broadway at 23rd to 24th streets launched a new hotel district along Broadway. Though the Fifth Avenue Hotel is gone, six others survive in the district, dating from 1890. Last and largest was the Prince George, surviving on 28th Street (Howard Greenley, 1904-05). The Victoria Hotel (demolished), built 1870, was the area's first luxury apartment building on Fifth Avenue. The Queen Anne style, seven-story Black Building at 251 Fifth Avenue (George B. Post, 1872) survives today as one of the city's earliest apartment buildings. Various multiple dwellings followed, including apartment houses, French Flats, and bachelor apartments.

From 1870 to 1910, the area around Madison Square became famous as an entertainment district. Broadway north of 23rd Street was one of the first parts of the city to have electric street lights, and by the 1890s had become known as the "Great White Way." The area boasted famous restaurants and theaters on or near Broadway. This period also saw the area become home to dozens of exclusive men's clubs, most in converted row houses.

Even as the entertainment district blossomed in the post-Civil War period, commercial interests made inroads into the area. Major retailers including Macy's and B. Altman's moved north from the Ladies Mile corridor heading towards Herald Square and 34th Street. Wholesale merchants followed, and speculative buildings – at first no more than 6 stories tall, but soon reaching from 12 to 18 stories – rose in the historic district to meet the demand for space; many such buildings combined stores at the ground floor with offices or lofts above. After 1890, commercial highrises became common in the district along Broadway and Fifth Avenue. Several industries made particular inroads into the new commercial precincts, including photography, architecture, and the building trades.

Many of the commercial buildings were designed by prominent architects. Among the earliest was No.1180 Broadway, a five-story, Neoclassical style, cast-iron fronted building designed by Stephen Decatur Hatch and built in 1870. Another early building was the Astor real estate office at 21 West 26th Street, a small, red-brick, Queen Anne style structure designed by Thomas Stent and built in 1883.

The taller buildings began going up in the early 1890s. Many had Classical Revival facades with elaborate ornament in stone, brick and terracotta. In several cases, the prominent architects who designed these buildings then moved in as tenants – Cyrus Eidlitz at the Townsend Building, on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 25th Street, built in 1896, and Bruce Price at the St. James Building, at 1133 Broadway, built 1896-98. Other architects doing work in the district – if not actually moving in – included Schickel & Ditmars, William L. Rouse, Francis H. Kimball, Maynicke & Franke, and Buchman & Fox. During the years just before and after World War I, many such architects turned to eclectic styles including the neo-Gothic. Among the last buildings to be constructed in the district was a 28-story-tall Art Deco tower on Fifth Avenue at East 28th Street, built in the late 1920s to designs by Ely Jacque Kahn of Buchman & Kahn.

After 1900, the commercial transformation of the district attracted a number of financial institutions as well. The ground floors of several office buildings were converted into Neoclassical quarters for bank use by such architects as John Duncan (208 Fifth Avenue, for the Lincoln National Trust, 1902), and Townsend, Sternle & Haskell (206 Fifth Avenue, for the Emigrant Savings Bank, 1919). Brand new buildings designed specifically for banks include the Lincoln National Trust's new home at 204 Fifth Avenue, a 1913 Beaux-Arts design by C.P.H. Gilbert, and the five-story tall, Neoclassical, Second National Bank of the City of New York built in 1907-08 to designs by McKim, Mead & White.

The proposed expansion adds approximately 150 buildings to the existing historic district. These buildings reflect the character of the existing district in development patterns, styles, building types and architects. Like those in the existing district, they range from pre-Civil War row houses to turn-of-the-century hotels to early 20th century loft and commercial buildings. Though they vary in size and design – styles range from the classically-inspired to the Moderne to the strictly utilitarian – together they have a clearly recognizable physical presence, and create a sense of place quite distinct from other parts of Midtown Manhattan.

The proposed expansion would extend

the district in several directions:

To the southwest, on the south side of West 26th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue; the north side is currently in the existing district. The expansion, extending the district to the south side of the block, would add six buildings adjacent to – but not including – an individually designated landmark (Trinity Chapel complex, now the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava). An option is to extend the boundary to the north side of West 24th Street, just opposite the northern boundary of the Ladies Mile Historic District, including the church, and also the mid-19th-century Worth Monument adjacent to Madison Square.

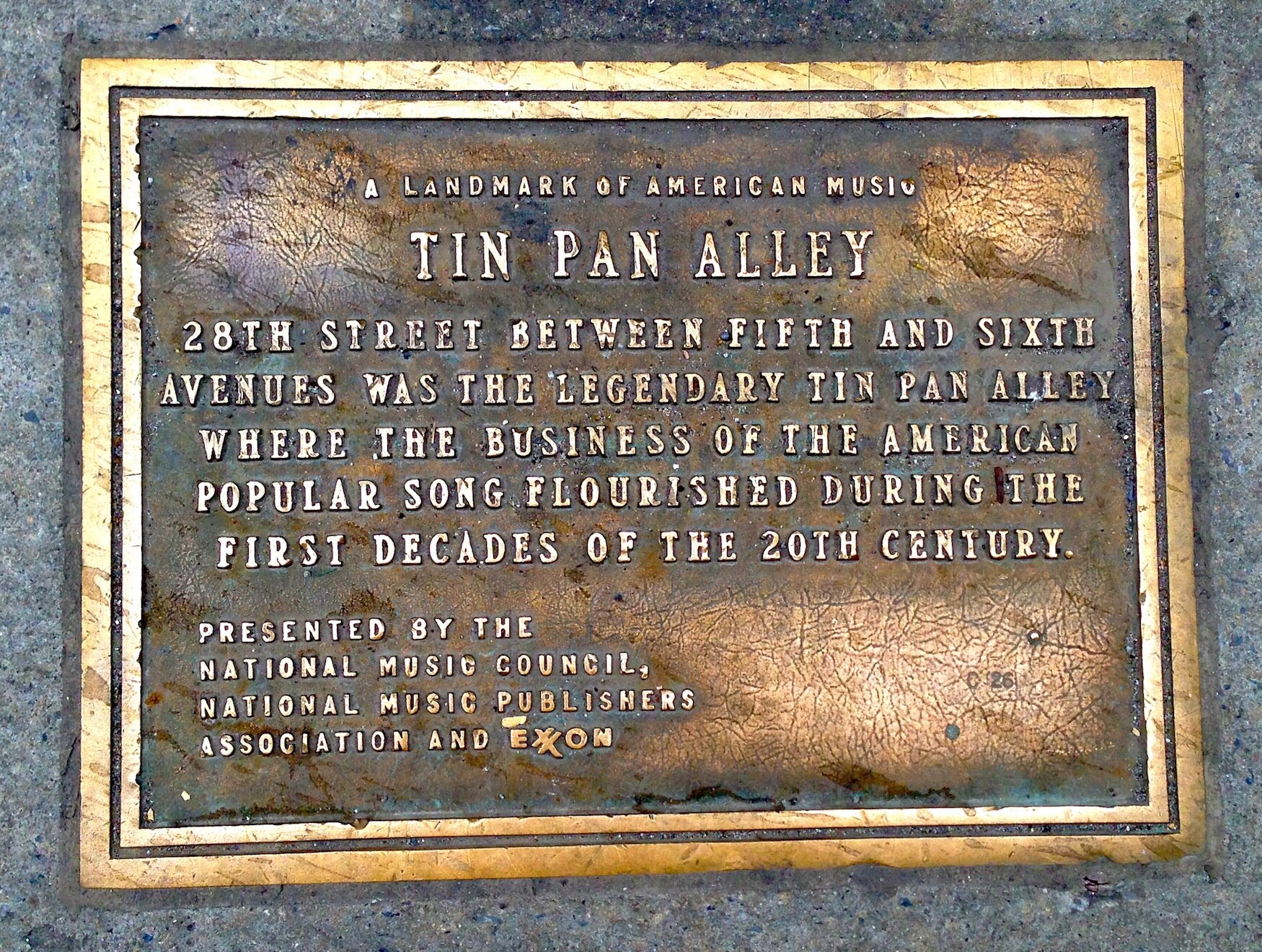

To the west, on the block of West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, currently outside the existing district, the expansion would add the north and south sides of the block extending to Sixth Avenue. This block is lined with low-rise buildings – including a number of Italianate row houses, dating from the very early 1850s – that once housed the musical industry known as “Tin Pan Alley.”

To the east, extending the boundary to the west side of Madison Avenue, between East 28th and 29th streets, squaring off that block. This would add five buildings to the district, three of which were built as turn-of-the-century hotels – a common building type in the existing district. An option would extend northward one block to include the Seville Hotel and one other building.

To the north and east, the largest portion of the proposed expansion, extending from West 29th Street to West 33rd Street, between Fifth Avenue and Broadway (and including one small block between Broadway and Sixth Avenue from West 31st to 32nd streets), and including portions of the blocks between Fifth and Madison Avenues from East 29th to 32nd streets. These blocks are lined with pre-Civil War row houses, late 19th century office buildings, turn-of-the-century hotels and early 20th century loft and office buildings, many of very high quality. Two options would add half-a- dozen buildings in the blocks east of Fifth Avenue.

The buildings in the proposed expansion include:

Twenty-three row houses, 18 of them pre-Civil War era and some dating from as early as 1848 – one year after the opening of Madison Square – most of them Italianate in style.

A dozen turn-of-the-19th-century hotels, most of them either neo-Renaissance or Beaux-Arts in style, by architects including John Duncan, Henry Engelbert, Henry Hardenbergh, Harry B. Mulliken, Neville & Bagge, and Ralph Townsend

Approximately 30 pre-World-War-I era loft buildings, mostly neo-Renaissance in style, by architects including George and Edward Blum, Buchman & Fox, Clinton & Russell, Gronenberg & Leuchtag, Hoppin & Koen, Thomas W. Lamb, Charles B. Meyers, George F. Pelham, Rouse & Goldstone, and Ralph Townsend

Approximately 40 other commercial buildings, including a late cast-iron facade by John B. Snook Sons

Approximately twenty office buildings from the 1910s and 1920s, by architects including James B. Baker, Carrere & Hastings, William I. Hohauser, Robert Maynicke, Rouse & Goldstone, Schwartz & Gross, Starrett & Van Vleck, in styles including neo-Renaissance, neo-Tudor, and Art Deco.

Together they complement the buildings of the existing district forming a natural extension to it.

SPECIAL CULTURAL AND HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE

Tin Pan Alley: The block of West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue became known as “Tin Pan Alley,” and functioned as the heart of the American popular music publishing industry from the early 1890s until just before the outbreak of World War I. A special appendix at the end of the report outlines the history and the connections to surviving buildings.

Photography history: In the first decades of the 20th century, this area housed a number of photographers, photography studios and galleries, and photographer organizations. Many buildings had skylights installed for the specific purpose of lighting photography studios. The Society for the Architecture of the City has gathered much information on this topic. In the building list that follows, the most notable photographic connections are mentioned.

SUPPORT THE CAUSE

There are several ways you can lend your support:

Join us to develop special programs highlighting the history of Tin Pan Alley.

Subscribe to our Neighborhood News email list and you will always be “in the know”.